YORUBA ORI-INU (INNER HEAD)

5.5" high x 3.5" wide x 3,75" deep

$600

SOLD

This rare leather, cloth and cowrie shell ori-inu (Inner Head) has been vetted as old and authentic.

--from African Shapes of the Sacred: Yoruba Religious Art by Carol Ann Lorenz, Senior Curator,

Longyear Museum of Anthropology, Colgate University.

Longyear Museum of Anthropology, Colgate University.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The Yoruba Metaphysical Concept of Ori

By awo dino

In Yoruba theology, perhaps nothing is more complex than the metaphysical concept of Ori, variously associated with the physical head (the cranium), personal Orisa, consciousness, destiny, human soul, and ancestral guardian angel. It can be considered as the Yoruba theory of consciousness, or as the Yoruba theory of destiny, or both. Our Ori serves as an umbilical cord connecting human with God (Olodumare). In order to begin to understand the Ori complex, we must start at the beginning, the Yoruba creation myth.

There are variations to the myth, and in fact there really are two separate story lines. One is cosmogenic and the other is political. The two became entwined into the most popular version below. Suffice to say at this point, the Ori (head) is to an individual what Olodumare is to the cosmos and a king to the body politic - a source of power. Hopefully, this paper while explaining the concept of Ori, will also provide a better understanding of the metaphysics of religious discourse; in this case the Yoruba religion.

Yoruba creation myth

Orisanla’ (Obatala’) was the arch-divinity who was chosen by Olodumare, the supreme deity to create a solid land out of the primordial abyss that constituted the earth and of populating the land with human beings. He descended from Orun (the invisible realm, the realm of the ancestors) into Aiye (the visible realm) on a chain, carrying a snail shell full of earth, palm kernels and a five-toed chicken. He was to empty the content of the snail shell on the water after placing some pieces of iron on it, and then to place the chicken on the earth to spread it over the primordial water by doing what chickens do, which is to scratch at the ground. According to this version of the myth, Obatala completed this task to the satisfaction of Olodumare. He was then given the task of making the physical body of human beings after which Olodumare would give them the breath of life (emi). He also completed this task and this is why he has the title of "Obarisa" the king of Orisas.

The other variant of the cosmogenic myth does not credit Obatala with the completion of the task. While it concedes that Obatala was given the task, it avers that Obatala got drunk on palm wine even before he got to the earth and he fell asleep. Olodumare got worried when he did not return on time, so he sent Oduduwa, Obatala’s younger brother, to find out what was going on. When Oduduwa found Obatala drunk, he simply took over the task and completed it. He created land. The spot on which he landed from Orun and which he redeemed from water to become land is called Ile-Ife, considered the sacred and spiritual home of the Yoruba. Obatala was embarrassed when he woke up and, due to this experience, he made it a taboo for any of his devotees to drink alcoholic beverages. Olodumare forgave him and gave him the responsibility of molding the physical bodies of human beings out of clay (in another version, Obatala was drunk when making the bodies and some came out a bit off. That is why Obatala is the Orisa of hunchbacks, and the disabled in general as well as albinos).

The making of land is a symbolic reference to the founding of the Yoruba kingdoms, and this is why Oduduwa is credited with that achievement. Oduduwa’s progeny were sixteen in number and became Kings. So Oduduwa was the first king of the Yoruba nation and founded Ile Ife, the ancient capital, creating a succession of kings all related to him.

However, this version incorporates history into the creation myth. It establishes the divine nature of the founder Oduduwa. Before the time of Oduduwa, the story did not involve Obatala getting drunk and Oduduwa finishing the job. What is important is the symbolism. The chain is representative of Ogun, the five toed chicken Osun, and the palm kernels, Orunmila. These Orisa, in combination represent unity and a balance of forces. Unity and balance (in a cosmos of dualities and diversity) become the central paradigm of Yoruba metaphysical thought. In Awo Fatunmbi’s words:

The world begins with one … the one that is formed through perfect balance between the powers of expansion and contraction, light and dark, … the balance between the masculine and feminine powers … and that one is a microcosm of all that is…

He has compared the chain to the double helix of DNA and the pieces of iron to Ogun as the primer of evolution. According to modern science, iron molecules at the bottom of the ocean are believed to have interacted with oxygen to create the first organisms on earth. Continuing the creation myth, Obatala was successful up to a point. He was unable to create civilization because he lacked the proper technology. Ogun was called in to continue the job. But Ogun, although very good at establishing civilizations, is not good at “running” them. In comes Orunmila to establish ethics and order; to temper Ogun’s primal energy. Obatala creates, but it is Ogun who moves creation, Ogun is evolutionary energy.

Keep in mind that Orisa and other entities featured in Yoruba myths, itan and Odu bear deep philosophical connotations that begin from the metaphysical meaning descending into the aesthetic and then epistemological through to ethical meanings and, eventually, to positive or negative social effects (it is easy to get caught up in the personalities themselves). Individual metaphysical phenomena come together as a unity of substances in a universe of relativistic existence (Okunmakinde). This idea is expressed in the most compelling part of the story; the Snail Shell full of earth-dust.

In the Odu Okanran Ogunda there is another version of the creation myth that is not well known. In this version, it is Orunmila (the Prophet, Orisa that represents Olodumare’s wisdom) who carries the snail shell full of the substance which creates land upon the primordial waters. The Snail Shell was taken from the seat of Olodumare and given to Orunmila with the authority to create the earth. In the process of creation, Orunmila dipped his hands into the snail shell and took out measures of earth-dust (Oro, primordial matter) with which land was created on the primordial waters.

Odu Ifa Osa Ogunda

There-were-no-living-things

Was the priest on earth

That-which-was-suspended

But-did-not-descend

Was the priest in heaven

All-was-just-empty-space

With-no-substance

Was the priest of Mid-Air

It was divined for Aiye and Orun*

When they both exited

With no inhabitants

In the two empty snail shells,

There were neither birds nor spirits

Living in them

Odumare then created himself

Being the Primal cause

Which is the reason we call Odumare

The only wise one in aiye

He is the only cause in creation,

The only wise one in Orun,

Who created humans.

When He had no companion,

He applied wisdom to the situation

To avert any disaster.

You, alone,

The only one in Orun

Is the name of Odumare

The only wise one,

We give you thanks,

The only knowing mind,

You created man.

Listening to one side of an argument,

You judge, and all are pleased.

Ase

*Aiye is the visible realm; Orun the invisible realm. Most confuse these two words to mean earth and heaven. Hopefully, when you finish reading this material, you will be able to come back and make sense of the above ese (verse) Odu.

In Odu Ifa Osa Ogunda, part of a verse says, “Iri tu wili tu wili la fi da ile aye, la bu da ile,” which means, “Dews pouring lightly, pouring lightly, was used to create the earth world in order that goodness could come forth into existence at once.” The dew drops are particles of Oro – primordial matter - contained in the snail shell. Once empty, it remains as the representation of the base of causation from which matter derived. The “goodness” speaks to eniyan – human beings, which brought goodness to earth. The oro then melted and was suspended in mid-air (referred to in the above Odu verse as the “priest of mid-air”). Oro then dropped;

Oro, the cause of great concern for the wise and experienced elders

It sounds, “Ku” (making the heart miss a beat)

“Ke” (as a ponderous object hitting the ground)

“Gi” (making the last sound before silence)

and “La”, with a loud cracking sound is transformed into a new state called “Ela.”

Ela is part of the Orunmila complex. Orunmila can be considered the anthropomorphic representation of Olodumare’s wisdom - ogbon, knowledge – imo, and understanding – oye; the most powerful particles or elements in the earth-dust or droppings. Orunmila’s connection to Ori is fundamental to the Ori complex. He is “Eleri Ipin”, the deity of fate. He was present at the moment of creation, and thus knows the fate of every Ori. He acts as the mediator between a person and their Ori through his ability to speak the words of Ifa as they relate to the individual Ori and its destiny. Ifa is the Oracle. Ela is that invisible energy that moves between the oracle and Orunmila, and between Ori and Olodumare – the umbilical cord. Ela is Oro after it hits the primordial abyss. Oro, as primordial matter, has an innate urge to communicate.

The oro that drops from the elderly is stupendous

It was divined for oro-oro-oro

Who did not have anyone to communicate with and started groaning

HOORO, HOO-ORO! (Ogbon, Imo, Oye, descend!)

Olodumare made HOO (Ogbon, Imo, Oye)

HOO descended to become Hoo-ro (I can’t help but notice the similarity between Hoo-ro and Horus)

Ela made Oro digestible and useful to human needs

Ela is the manifestation of the primal urge to communicate. It is the link between human and God; human and human; and human and the universe. This extensionistic conception, prevalent in all religions, is Oro, which manifested is Ela. Its individual manifestation is Ori. The Snail can be viewed as the principle of natural extensionism which forms a basis for that which can be seen and that which cannot; the physical Ori (your skull), and Ori-inu (consciousness, soul). There is a Yoruba phrase, Ori-Ooro, which means, “head at dawn,” dawn being the beginning obviously. Thus, Ori is Oro, and Oro is Ori:

Ori lo nda eni

Esi ondaye Orisa lo npa eni da

O npa Orisa da

Orisa lo pa nida

Bi isu won sun

Aye ma pa temi da

Ki Ori mi ma se Ori

Ki Ori mi ma gba abodi

Ori is the creator of all things

Ori is the one that makes everything happen, before life happens

He is the Orisa that can change humans

No one can change the Orisa

Ori, the Orisa that changes the life of man with baked yam (abundance)

Aye*, do not change my fate (* Aye - unity of the forces of good and evil)

Ori do not let people disrespect me

Ori do not let me be disrespected by anyone

My Ori, do not accept evil

This extensionalistic concept (from God to human), that our Ori is composed of a portion of Oro (each Ori receives a portion with its own special combination of elements contained in the earth-dust – oro - from the snail shell, thus each ori’s individuality) is further elucidated in the sayings, Ori lo da ni, enikan o d’Ori o (It is the Head that created us; nobody created the Head), and Ori eni, l’Eleda eni (one’s Head is one’s Creator), and also in the following oriki:

Ori lo da mi

Eniyan ko o

Olorun ni

Ori lo da mi

Ori is my Creator

It is not man

It is Olorun (Olodumare)

Ori is my Creator

Olodumare made Hoo, which is comprised of three of the most powerful elements contained in the “earth-dust” sprinkled from the Snail shell – Ogbon (wisdom), Imo (knowledge), and Oye (understanding). “Ro” means descend, as in the chant, Ela ro, Ela ro, Ela ro. It is said that Olodumare created Ogbon, Imo and Oye as an intermediary force for creating more beings. IT tried to find a place for them to live, but they came back to IT, humming, and Olodumare swallowed them. They hummed inside IT for millennia, so IT had to get rid of them. Olodumare ordered them to “ro” descend, saying, “hoo-ro.” Oro, the solid matter, melted and was suspended in mid-air like jelly. Oro then dropped and “la” cracked into a new state called E-la, or Ela. Ela (the Spirit of Purity) functions in the Ifa divination complex as the embodiment of Ogbon, Imo, and Oye. Ela is the recognized authoritative source of communication and explanation of the nature of Olodumare and all ITs creation (Abiodun).

Who was the first to speak?

Ela was the first to speak.

Who was the first to communicate?

Ela was the first to communicate.

Who is this Ela?

It was the Hoo which descended

That we call Ela.

In Odu Ogunda Ogbe, we find more references to Snail and Oro:

He Made Divination for the Snail in Orun

Aba she kere mu legun, Odifa fun ibikunle to ma nu kan kunle ara le

The-umbrella-tree-is-short-when-young-but-a-little-later-it-will-become-taller-than-the-roof-of-the-house. That was the name of the Awo who made divination for Ibikunle, when she was single-handedly going to populate her house by herself. Ibikunle is the heavenly name of the Snail and it means the one who produced enough children to fill his or her house. She was advised to make ebo with hen, rat and fish. She made the ebo and began to produce children to fill her house. When it appears at divination for a woman anxious to have children, she will be advised to make ebo because she will have so many children that she will eventually be tired of having more.

He Later Divined for his Friend Oro

Okon kpoki, Erigidí kpií, adita fun Oro nijo ti Oro wo orun kenge kenge.

One-sharp-sound and one-loud-sound (“Ku” and “Ke”)are the names of the Awos who made divination for Oro when he was so ill that he thought he was going to die, (figure of speech) when he was looking forlornly at Orun from his spot hanging in the air. He was advised to make ebo with eko, akara, rat, fish and a chicken. After preparing the ebo, the Ifa priests told him to carry it on his head (ori) to Esu’s shrine. He was further told that on getting to the shrine, he was to back it and incline his head backwards in such a way that the ebo would drop on the shrine (acknowledging Esu as that liminal space between orun and aiye, dark and light).

As soon as he allowed the sacrifice to drop on the Esu shrine, while still backing up to Esu, a voice instructed him to stretch his hands and feet forward. First, he stretched out his left limbs and next his right limbs (with Esu’s help, he makes the transition from the invisible plane to the visible plane. Left limbs darkness, right limbs light). The moment he did that, the disease that had afflicted his body to the point of incapacitation suddenly disappeared. From the shrine, he began to dance and sing towards the house in praise of the Awo. The Awo praised Ifa, and Ifa praised Olodumare. When he began to sing, Esu put a song in his mouth:

ljo logo ji jo, erigidi kpii, erigidi.

ljo logo ji jo, erigidi kpi-kpi-kpí, erigidí.

He was singing in praise of Orunmila and his two surrogates for the miraculous healing he had just experienced. When this odu appears at divination in ibi (negative manifestation) the client will be

told that he or she is suffering from a disease which he or she is concealing, but will be advised to

make ebo to get rid of it. If the indication is ire (positive manifestation), then the person will be told to be expecting some gift or favor.

In the ese (verse) above regarding Snail, we see that Snail is also known as Ibikunle, “the one who produced enough children to fill his or her house.” This is a praise name. It refers to the the Snail’s role in creating everything in the universe, in this case the earth including humans. In the verse following the one about snail, regarding Oro, we find in the names of the Awo, reference to the sounds of Oro dropping and becoming Ela (the Spirit of Purity which represents Ogbon, Iwo and Oye).

Ela speaks through Owe (proverbs, Odu, oriki, chants, ofo ase, etc.), and Aroko (coded symbolic messages- drums, sculpture, dance, song, poetry, etc.). Owe is the horse of Oro; if Oro gets lost, Owe is employed to find it.

ORÍKÌ ELA

Ela ro, Ela ro, Ela ro (ro – descend)

Ifa please descend

Ela, please be present

If you are in the Ocean,

please come

If you are in mid-lagoon,

Please come

If you are on the hunt,

Please come

Even if you are at Wanran in the East

Where the day begins

Please come

Come urgently, Ela

ase

The awo, or diviner, must develop the ability not only to invoke Ela, but to align Ori with Ela. Ela is that substance that is extensionalistic; that connects our inner self in the visible plane with our higher self on the invisible plane. The historical prophet Orunmila was an incarnation of the Spirit of Ela and the alignment of Ori with Ela is known as returning to the time when Orunmila walked the earth. This alignment occurs as a result of consistent attention to the Ifa discipline of chanting oriki (communication). Alignment with the Spirit of Ela is the blessing of Ifa and chanting is the road to that blessing (Fatunmbi). In order to work with one’s Ori, Ela must be invoked first.

The Ori complex

As we continue with the Yoruba creation myth, we now come to the creation of human beings. Obatala’ who is equally referred to as Orisa-nla’ (the arch divinity), is said to have been charged with the responsibility of sculpting the human being “eniyan” and designing only the body: hence his appellation a-da-ni bo ti ri (he who creates as he chooses). After finishing his work, Olodumare then breaths (emi – life force) life into the body. The eniyan then proceeds to Ajala-Mopin – Irunmole to o nmo ipin (the divinity who moulds ipin) ipin is that portion of oro, the “God-matter” apportioned to each Ori by Ajala-Mopin. Ipin is destiny. In Ajala’s “shop,” the eniyan (person) selects for himself his ipin (portion), commonly referred to as Ori-inu (inner head). Here we have the separation of body and mind, or soul. Presumably, the choice of heads (Ori) is based on what one wants to accomplish in the coming lifetime. This Ori–inu or ipin is the individual’s chosen destiny. There is some variance in this part of the myth. Some say you get your Ori from Ajala but then go to Olodumare and tell IT what you want to accomplish in this lifetime, and the deal is sealed. Some say that humans obtain their ipin (portion, destiny) in one of three ways; by kneeling down and choosing it, a-kun-le-yan (that which one kneels to choose), by kneeling to receive, a-kun-le-gba (that which one kneels to receive), or by having his destiny apportioned to him a-yan-mo (that which is apportioned to one). Others, myself included, believe akunleyan, akunlegba and ayanmo are component parts of Ori-Apere. (one half of Ori) Regardless, all acknowledge the Yoruba belief in predestination and also establish the belief in Ipin (portion) as a person's destiny which he chooses during his pre-existent state. It is this destiny that is seen as metaphysically constituted in Ori-inu (inner head) and it is this that man comes into the world to fulfill. This belief manifests itself in the maxim Akunle-yan ni ad’aye ba (the destiny chosen is that which is met and pursued) (Abimbola).

The Yoruba believe that creation exists on two complementary planes: the visible world, called aiye, the physical universe that we inhabit, and the invisible world, called orun, inhabited by the supernatural beings and the "doubles" of everything that is manifested in the aiye. These planes are not to be confused with heaven and earth. There is not a strict division; they exist in the same space. The aiye is a "projection" of the essential reality that processes itself in the orun. Everything that exists, exists in orun also. Actually, orun is the reality and aiye the mirror image. It is necessary to understand that aiye and orun constitute a unity, and as expressions of two levels of existence, are undivided and complementary. There is full identity between them; one is just an inverted image of the other (Teixeira de Oliveira).

The Ori complex is comprised of three parts; the Ori - Consciousness; Ori Inu - the Inner Self; and Iponri - the Higher Self. Much has been written regarding the concept of Ori. I break it down using the theory of extensionalism, which simply states that humans are connected to God in some manner; that there is communication; that we are in fact extensions of God. This idea is common to most metaphysio-religious systems. In Yoruba thought we have the concept of Oro. At the level of the individual, the concept is expressed in the Ori complex (or soul complex) – an extensionalistic construct that explains the interaction between tangible and intangible existences. As Orun and Aiye exist simultaneously in the same space, so does the human soul in the form of Ori-inu and Iponri. Matter-mass which makes the transition from orun to aiye through the snail shell produces a double existence. The fragments or portion that a person receives (ori-inu) from Ajala-Mopin in his or her Ori is brought with the person to aiye, the visible realm and to Ile (earth). The original stays in orun. This original is called the Iponri or Ipori. It is our Iponri that allows blessings to flow from “above.” No Orisa can bless us without permission from our Ori. Why? Because our Iponri is our real self, our beginning and our end. Any thing we wish to manifest in life, must be created by our Iponri first in the invisible realm, where all things are created before manifesting in the visible worlds. Thus the popular chant from Odu Ifa:

Ko soosa

Ti i dani i gbe

Leyin Ori Eni

No divinity

Can help, deliver, or bless one

Without the sanction of one’s Ori

Our wishes, wants, fulfillment of needs, prayers, etc., must originate in orun before they can manifest in aiye. Our Ori, the third component of the Ori complex, serves as our individual “Ela,” that which connects our dual selves that exist simultaneously in the invisible and visible worlds. Ori is that intangible substance that is the extension, the communication, across the divide. That is why we portray Ori as our personal Orisa, because Ori carries our prayers and communicates our wishes to our Iponri. In this way, our Ori is like an Orisa pot. It is our connection to ase. This is why Ori is the first “Orisa” to be praised (Ori isn’t really an Orisa), it is the one that guides, accompanies and helps the person since before birth, during all life and after death, assisting in the fulfillment of his or her destiny. Ori-Apesin; one who is worthy of worship by all. It is said that a person’s Ori, besides being the source of ire, is the only Orisa that can and will accompany one to the very end:

Bi mo ba lowo lowo

Ori ni n o ro fun

Orii m, iwo ni

Bi mo ba bimo l’aiye

Ori ni n o ro fun

Orii m, iwo ni

Ire gbogbo ti mo a ni l’aiye

Ori ni n o ro fun

Orii m, iwo ni

Ori pele

Atete niran

Atete gbe’ni k’oosa

Ko soosa ti I da’ni I gbe

Leyin Ori eni

Ase

It is Ori alone

Who can accompany his devotee

to any place without turning back

If I have money, it is my Ori I will praise

It is my Ori to whom I shall give praise

My Ori, it is you

All good things I have on Earth

It is Ori I will praise

My Ori it is you

No Orisa shall offer protection

without sanction from Ori

Ori, I salute you

Whose protection precedes that of other Orisa

Ori that is destined to live

Whosoever’s offering Ori chooses to accept

let her/him rejoice profusely

Ori the actor, the stalwart divinity

One who guides one to wealth, guides one to riches

Ori the beloved, governor of all divinities

Ori, who takes one to the good place

Ori, behold the good place and take me there

Feet, behold the good place and accompany me thereto

There is no divinity like Ori

One’s Ori is one’s providence

My Ori, lead me home

My Ori, lead me home

Ori, the most concerned

My skull, the most concerned in sacrificial rites

Ori, I thank you

Ori, I thank you for my destiny

My skull, I thank you for my destiny

Ori I thank you (mo juba)

Ase

As the “personal Orisa” of each human being, our Ori is vital to the fulfillment and happiness of each man and woman; more so than any other Orisa. More than anyone, it knows the needs of each human in his or her journey through life. Ori has the power of Ela, to pass freely from Orun to Aiye and vice versa. It exists on both dimensions:

Ire gbogbo ti ni o nii

N be lodo Ori

A lana-teere kan aiye

A lana-teere kanrun

All the good that I am expecting is from my Ori

He who makes a narrow path to aiye

He who makes a narrow path to orun

What at first glance seems like a very complicated theology, when we gain an understanding of the metaphysics within the mythology, reveals a simple metaphysical principle; the principle of causation. The ability to create in Orun, and have it manifest in Aiye; like Oro becoming Ela. Awo is the development of this ability; either through our Ori, through Orisa, ancestors, etc. Others have expressed the concept of Ori. One explanation worth quoting is by Babasehinde Ademuleya:

"The soul, to the Yoruba, is the “inner person”, the real essence of being – the personality. This they call “ori”. The word “ori”, in contrast to its English meaning as the physical “head”, or its biological description as the seat of the major sensory organs, to the Yoruba connotes the total nature of its bearer. A critical study of the term in Yoruba belief reveals the intrinsic meaning and value of the object it is identified with – that is, the physical head – and carries with it the essential nature of the object associated with it – that is the man. To the Yoruba the physical “ori” is but a symbol – a symbol of the “inner head” or “the inner person”, the “ori-inu” (the inner head). Ori in Yoruba belief occupies the centre of sacredness, and how it is conceived is embedded in the Yoruba myth concerning the creation of man and the role played by his creator, Eledaa (He who created). The Yoruba word for man – eniyan – is derived from the phrase eni-ayan (the chosen one)."

… a wa gegebi eniyan, …

a wa ni Olodumare yan

lati lo tun ile aye se,

Eni -a yan ni wa...

we as human beings,

we are the God’s elect,

designated to renew the world,

We are the chosen ones.

Human beings are called eniyan (the chosen ones) because they are the ones ordained "to convey goodness" to the wilderness below Olorun. In other words, divinity abides in humanity, and vice versa.

Let us now consider the Ori-inu. The African idea of the soul has been conceived and described in different ways. In Yoruba, the idea of the transcendental self, or soul, has been difficult to express in English. Some have called emi soul. Emi is invisible and intangible. This is the life force breathed into each human by Olodumare. Not to be confused with eemi, which is simply breath. Emi is what gives life to the body. When it ceases, life ceases. A Yoruba would say about a corpse, “emi re ti bo” - his emi is gone. But it is not soul. Another word sometimes mistaken for soul is okan, which literarily means the heart. For the Yoruba, the heart is more than an organ that pumps blood. It is from where our emotions emanate, and the locus of psychic energy. But it is not soul. Both of these interpretations are wrong. The soul, to the Yoruba, is Ori-inu, that portion of the “God-stuff” from the Snail that comprises the “inner person”, the real essence of being.

Regarding life-force, that which Olodumare bestows on each individual and an integral component of each Ori-inu, it is known as ase (pronounced awshay). Emi is the life force, but it is made up of ase. Ase is a concept almost as complex as Ori. Ase is a component of the life force breathed into each human being by Olodumare; it is spiritual power; it is the power to create. Pemberton describes it this way:

"Ase is given by Olodumare to everything – Gods, ancestors, spirits, humans, animals, plants, rocks, rivers and voiced words such as songs, prayers, praises, curses, or even everyday conversation. Existence, according to Yoruba thought, is dependent upon it; it is the power to make things happen and change. In addition to its sacred characteristics, ase also has important social ramifications, reflected in its translation as “power, authority, command.” A person, who through training, experience, and initiation, learns how to use the essential life force of things is called an alaase. Theoretically, every individual possesses a unique blend of performative power and knowledge – the potential for certain achievements. Yet, because no one can know with certainty the potential of others, eso (caution), ifarabale (composure), owo (respect), and suuru (patience) are highly valued in Yoruba society and shape all social interactions and organization.

Ase inhabits the space (shrine) dedicated to Orisa, the air around it, and all the objects and offerings therein. As stated by Pemberton, ase pertains to the identification, activation and use of the distinct energy received by each thing in its original portion. The efficacious use of ase depends on the ase and knowledge, the awo, of the one who attempts to harness it. The power of the word is an important part of harnessing ase."

The day Epe was created

Was the day Ase became law

Likewise, Ohun was born

The day Epe was invoked

Ase is proclaimed

Epe is called

But they both still need Ohun (to communicate)

Without Ohun (voice), neither Epe (curse, the malevolent use of ase), nor Ase can act to fulfill its mission. This is why ase is often likened to a-je-bi-ina (potent and effective traditional medicinal preparations which respond like the ignited fire (ina). Je (to answer), da (to create), and pe (to call). Iluti is the power of the Orisa to respond to our call – Ebora to luti la nbo – we worship only deities that can respond when consulted (Abiodun). One of the main goals of Ifa/Orisa devotees is to build up their personal ase. The goal of every babalorisa, iyalorisa, santera, santero, iyanifa and babalawo (collectively called Awo), is to not only build up their personal “quantity” of ase, but to develop the ability to tap into the ase of other beings and objects in order to use it.

"Awo need to develop the ase necessary to transform ibi (misfortune) into ire (good fortune). They must possess the ability to effect change in the visible world by manipulating forces in the invisible world. “The word “Ela” literally means “I am light” from the elision e ala. The ability to become one with the Spirit of Ela is the ability to use Ori as a portal between the visible world and the invisible world. When an Awo is in an altered state of consciousness the thing that passes between dimensions is pure unformed ase symbolically referred to as ala or white light. As this ase comes from Ile Orun to Ile Aiye through the Ori of the diviner, it takes shape and is formed by the ofo ase inherent in the oriki spoken by the diviner while in an altered state of consciousness” (Fatunmbi).

The innate urge to communicate contained in Oro and manifested as Ela is observable ritual. The importance of Esu cannot be overstressed, as it is Esu who determines the efficacy of any ritual, from iwure (prayer), to chanting Odu verses (oriki ire), to ebo and to initiation ceremonies. Esu is in a powerful position as one’s good fortune or bad depends on what he “reports” to Olodumare. A hierarchical structure emerges in divine communication. Even if Esu carries the message of an Orisa to Olodumare, Olodumare will check with one’s Iponri (higher self, twin soul in Orun) to see if it has the desired ire (good fortune) asked for by the person. If the person’s Iponri says yes, then Esu delivers the message to the original Orisa who made the request on behalf of the person. Esu facilitates the movement from orun to aiye as he is the line in between them. Esu and Ela are inseparable.

Another aspect to divine communication is the use of color. The use of color against color creates a mathematical equation. This graphic design uses symmetry, rhythm, emotion, and balance, creating a sense of wonderment. The Yoruba word for this is iwontunwonsi (moderation). An example would be the white and red of Sango. The red signifies raw power, and heat. The white coolness and wisdom. Sango is balanced, moderated – iwontunwonsi – through color. This concept is expressed In the following Yoruba saying derived from Odu: Efun ewa osun l'aburo Beautiful lime chalk (white) is camwood's (red) senior (Mason). The Yoruba metaphysics of extensionalism, is a somewhat complicated structure of divine communication, but a close relationship between all involved (Ori, Esu, ancestors, Orisa, etc) insures its efficacious nature.

In addition to controlling the release of ire, our Iponri determines the Odu under which we are born, which in turn determines which Orisa energy a person will live under in the particular life in question (Orisa are born in Odu). When we tell Olodumare what kind of experiences we want to have in a lifetime, we are choosing experiences that will help us hone our souls; we want to work on our weaknesses. Thus Olodumare will place us under the influence of the particular Odu/Orisa that will best provide us with those experiences.

The concept of personal taboos (ewo) in Ifa/Orisa is related to our dual existence (ori-inu as double of iponri) A person should not ingest or have anything to do with the particular elements (including colors) that make up his or her ipin, or portion (ori-inu) (Opefeyitimi). These ewo are contained in the Odu of our birth. It is through divination (“Da’Ifa or Dafa – da – to create) that we learn what we need to know about our Ori, Odu, taboos, destiny, potential pitfalls, dangers, etc.

For further explanation of Ori-inu, ase, and Iponri we return to Fatunmbi:

In Yoruba psychology, consciousness originated from lae-lae (i.e. eternity)—the mystical source of creation. This idea is part of a body of thoughts on the structure of being and of the universe, and these thoughts are referred to as Awo (i.e. secrets). These ideas were formulated at the dawn of Yoruba civilization, and were contained in 256 verses each known as an Odu. Knowledge of these ideas was kept away from the public domain and guarded jealously by the priests of Ifa (the Yoruba religion). They were only passed on via oral tradition from one priest to a descendant priest. It is only recently that some of these ideas have started to be written down by Yoruba scholars.

According to Awo, a part of which is paraphrased above, everything in the universe was created from the ontological tension between the opposing forces of expansion and contraction, light and darkness. The contracting forces are centripetal in nature, and therefore absorb light, and the expanding forces are centrifugal and so generate light.

To the Yoruba, light comes from darkness and darkness from light. Both are seen as an expression of ase, a spiritual potency sustaining all of creation. In human beings, the seat of ase is located within ori-inu (i.e. inner head), which is the spiritual consciousness of self and the home of the unconscious mind. The balance of opposing energies in ase generates a spherical pattern in consciousness. This is symbolized by the circular format of opon-ifa, a divination board used by priests to restore alignment between ori (i.e. the physical head, also the seat of the conscious mind) and iponri (i.e. the super-soul, imbued with eternal life, which resides in orun). This board is essentially a map of the polarities of forces in consciousness.

Referring to the opon-ifa model of the structure of consciousness , ori is to the south, opposite iponri in the north. To the east is ara (i.e. the body) and to the west is emi (i.e. soul). In the center of these forces is the inner head (ori-inu). It is the home of the unconscious mind and the seat of destiny.

It is believed that, just before birth, every ori (i.e. consciousness or head) negotiates an agreement with Olorun (i.e. God—literal translation is owner of the sky), outlining their goals for that lifetime. At birth the details of this agreement are removed from the realm of conscious thought and hidden in the unconscious domain, within the inner head (ori-inu) and iponri in heaven. One's destiny, therefore, is to remember the original agreement and work towards achieving those goals. Any deviation from these goals creates a misalignment between iponri and ori and results in disease. Healing is sought through divination, a process of remembering and of realignment with destiny.

This is a very lucid explanation and worthy of including in its entirety; although, I disagree with the formulation of emi as soul. What we want to accomplish through divination and in our daily lives, is the balance of the four quadrants which intersect at Ori–inu, the center spot on the opon Ifa. It is worthy to note at this time that the Ori-inu is also the interstice of all Orisa. Obatala (the arch-divinity) came down the chain with the Snail Shell. Ogun not only took over where Obatala left off, but also works alongside Ajala-Mopin. Ogun, carves the faces of the Ori’s after Ajala moulds them, including the eyes, which are then “activated” by Esu, who also activates the facial muscles, in effect giving us the emotions. Remember also, that Esu is the “membrane” between darkness and light. Ogun’s relationship to Ori is found in still another Odu verse from Osa Meji:

Ori buruku ki i wu tuulu

A ki i da ese asiweree mo loju-ona

A ki i m' ORI oloye lawujo

A da fun Mobowu

Ti i se obinrin Ogun

Ori ti o joba lola

Enikan o mo

Ki toko-taya o mo pe'raa won ni were mo

Ori ti o joba lola

Enikan o mo

A person with bad head (Ori) isn’t born with a head different from the others

No one can distinguish the footsteps of the madman on the road

No one can recognize the head destined to wear a crown in an assembly

Ifa was cast for Mobowu,

Who was the wife of Ogun

A husband and a wife should not treat each other badly

Not physically, nor spiritually

The head that will reign tomorrow,

Nobody knows

The participation of Obatala and Ogun in creation is attested to by the fact that most of the ese Odu about creation are found in Odu’s containing either Ogbe or Ogunda or a combination of both (Ogbe is the Odu that incarnates Obatala, and Ogunda incarnates Ogun).

Osun is the “owner of the beaded hair comb,” and the Orisa of hair stylists. Besides adding to the power and beauty of the human face and head which is the focus of much aesthetic interest in Yoruba culture and art, hair-plaiting carries an important religious significance in Yoruba tradition. The hair-plaiter (hairdresser) is seen as one who honors and beautifies Ori, the “pot” for Ori-inu. One’s head is taken to be the visible representation of one’s destiny and the essence of one’s personality. It is believed that taking good care of one's hair is an indirect way of currying favor with one's Ori Inu. Thus, the Yoruba have created a wide range of hairstyles that not only reflect the primacy of the head but also communicate taste, status, occupation, and power, both temporal and spiritual.

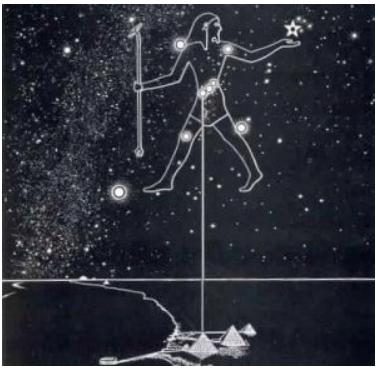

Yoruba religion focuses on the worship of the Orisa because of the belief that they act on behalf of Olodumare, who is too exalted to be approached directly. Yet Olodumare is indirectly involved in the day-to-day life of an individual through his/her Ori Inu, which is also called Ori Apere. This is why it is of central importance to maintain balance and harmony between the three components (ori, ori-inu, iponri) of the Ori complex. This preoccupation over rides any worship of any Orisa, and even of one’s ancestors. In the past, every adult Yoruba had an Ori pot or an ibori, which is kept inside an ile ori (house of the head). It is encased in leather and adorned with as many as 12,000 cowrie shells.

Many people consider the Yoruba concept of Ori as fatalistic. If one’s Ori contains one’s destiny, which is pre-determined in Ajala-Mopin’s workshop, then how can it not be fatalistic? If every activity we engage in on earth has been pre-ordained at the point when we chose our ipin-ori (portion or lot) with Ajala-Mopin before coming into the world and cannot be altered, then how is it not a fatalistic theology?

The first thing to consider is that Ori is divided into two parts; Apari-inu (represents character) and Ori-apere (represents destiny). So far we have only considered Ori-apere. This division into two parts is why, at the beginning of this paper, I said, “It can be considered as the Yoruba theory of consciousness, or as the Yoruba theory of destiny, or both,” and is the source of much confusion regarding the Ori complex. As stated previously, Ori-apere, the half that consists of destiny, consists of three elements: a-kun-le-yan (choice), a-kun-le-gba (freewill) and a-yan-mo-ipin (destiny)

Akunleyan were choices you made at the feet of Olodumare regarding what experiences you wanted on earth. For example, how long you wanted to live, what kinds of successes and failures you wanted, the kinds of relatives, etc. Why not choose to be the only child of wealthy parents? Because life is not measured on how comfortable it was, but on the degree of honing of the self that was accomplished; The continuing quest for perfection; the elevation of soul. Akunlegba (notice legba in the phrase) is the element of free will. The freedom to make choices while on earth. Watch out, Esu/Legba is watching! Akunlegba also relates to those things given to us to help us fulfill the choices made in Akunleyan. Ayanmo is that part of our destiny that cannot be changed. For example, our sex, the family in which we are born, etc. But even here, in Ajala-Mopin’s domain, we make a choice as to which of the Ori’s we want. It is when coming into the world, when we pass through omi-igbagbe – the water of forgetfulness; the boundary between orun and aiye (Esu), that we forget our chosen destiny.

These concepts show that although there is some determinism involved, there is plenty of room for one to influence one’s fate. There is another element called ese. Ese literally means “leg,” but in this context means “strife,” “hardwork,” or “struggle.” Ese introduces the principle of individual effort:

Opebe the Ifa priest of ese (legs)

Divined for ese on the day he was coming from Orun to Ile (earth)

All the Ori’s called themselves together

But they did not invite ese

We will see how you will bring your request to fruition

Their meeting ended in quarrel

They then sent for ese

It was then that their meeting became successful

That was exactly as Ifa had predicted

No one deliberates

Without reckoning with ese

Opebe, the Ifa priest of ese

Cast Ifa for ese

On the day he was coming from Orun to Ile

Opebe has surely come

Ifa priest of ese

ase

This principle is further elucidated in a verse of EjiOgbe:

"Do your work"

"I am not working"

This was the Ifa cast for the lazy person

He who sleeps until the sun is overhead

He who relies on that which is possessed through inheritance

exposes himself to suffering

If we do not toil and sweat profusely today

We cannot become wealthy tomorrow

"March through the mud"

"I cannot march through the mud"

"If we do not march through the mud

Our mouths cannot eat good food"

These were the declarations of Ifa to the lazy person

He who possesses strong limbs but refuses to work

He who chooses to be idle in the morning

He is only resting for suffering in the evening

Only toiling can support one

Idleness cannot bring dividend

Whoever refuses to work

Such a person does not deserve to eat

If a lazy person is hungry, please let him die

Dead or alive, a lazy person is a useless person

Besides not working hard, another path to failure is that in which a person, not knowing their destiny, will work against it, thus experiencing futility even if working hard. This is why we turn to Ifa through Orunmila – Eleri-ipin, for guidance as to whether or not one is on the right path. However, one is free to make use of ese (hardwork) and ebo (sacrifice, offerings) – which requires freewill – to change their fortunes. Since Ori is limited to one’s material success – nowhere in Odu does it say that Ori pre-determines moral character or personal ethics - it does not affect all our actions. Although we come into the earth with either a good Ori – olori-rere (owner of a good Ori) – or a bad one – olori buruku (owner of a bad Ori) – an individual’s destiny can be changed through the help of spiritual forces such as Orisa, Egun, etc. Ebo is a form of communication between the natural and supernatural realms, and involves the establishment of a reciprocal relationship with those forces. One’s destiny may also be affected by the Ajoogun - malevolent forces. In addition, there is a concept called afowofa, were one is the cause of one’s own problem. Such actions are empirically observable. So a person is held responsible for those actions for which he is the cause, but attributes to his Ori those which transcend him (Balogun).

Orunmila lo dohun a-dun-hun-un

Emi naa lo dohun a-dun-hun-un

Orunmila ni begbe eni ba n lowo

Ba a ba a ti i ni in

Ifa ni ka ma dun huun-huun-huun

Ori elomii mo

Ori eni ni ka maa dun huun

Orunmila ni begbe eni ba n n’ire gbogbo

Ba a ba a ti I ni in

Ori eni ni ka maa dun hun-un

Orii mi gbami

Mo dun huun aje mo o

Orii mi gbami

Mo du huun ire gbogbo mo o

Ori apere

a-sakara-moleke

eni Ori ba gbebo re

ko yo sese

ase

Orunmila said complaint, complaint, complaint…

I said it is all complaint

Orunmila said if ones colleagues are rich

If we are not yet rich

Ifa said we should not complain

To another person's Ori

We should complain to our own Ori

Orunmila said if one's colleagues are getting

all the good things of life

If we have not got...

We should complain only to our Ori

My Ori, deliver me

I complain of money to you

My Ori deliver me

I complain of all the good things of life to you

Ori nicknamed apere. Nicknamed A-sakara-moleke

Whoever’s offering is accepted by their Ori

Should really rejoice.

Ase

Orunmila’s involvement in the Ori complex cannot be overstressed. One of his praise names is A tori Eni ti ko sunwon se - One who reforms bad heads. In Odu Ogbe Ogunda, Ifa says there were seven duties one had to perform before he left orun for aiye or ile:

1. Divination

2. Performing of Ebo

3. Job distribution and giving of Ewo (taboos)

4. Digging the pit of loss

5. Removing the rag of poverty

6. Wishes

7. Choice of Ori

According to the Ifa verse, these duties takes place at four different locations. Perhaps relating to the four parts of the opon Ifa. These duties together comprise ipin – destiny. However, we forget our destiny on the way out of the birth canal. This makes it extremely difficult to complete our destiny. However, Orunmila, as Eleri-ipin (witness to destiny) through Ifa, can help us make the necessary corrections in our lives to get back on path.

In Ogbe Ogunda, IFA says:

A grinder makes three works

It grinds yam

It grinds indigo plant

It is used as a lock behind the door

cast Ifa for Oriseku, Ori-Elemere and Afuwape

When they were about to choose their fates in the domain of Ajala-Mopin

They were told to make ebo

Only Afuwape made the ebo requested

He, consequently, had ire gbogbo (all good fortune)

The others lamented, they said that if they had known where

Afuwape had gone to choose his Ori

they would have gone there to choose theirs

Afuwape answered that, even if they had chosen their Ori’s

in the same place, their fates would still have differed

Only Afuwape had shown good character. By respecting his elders and doing his ebo, he brought the potential blessings within his destiny to fruition. His friends Oriseku and Ori-Elemere had failed in showing good character in refusing to make ebo and, because of that, their destinies were altered. The most important influence on one’s destiny is one’s character and personal ethics – iwa. Iwa pele, or iwa rere, good or gentle character. That’s why the Yoruba say, “the strongest medicine against curses and spells is iwa pele.”

Here we come to the end of the philosophical movement from the metaphysical meaning descending into the aesthetic and then epistemological through to ethical meanings and, eventually, to positive or negative social effects. The ethics of iwa pele – good character. If your life is a mess, before blaming witchcraft, family, or co-workers, examine your nature, your character. If you are selfish; if you are arrogant, if you are disrespectful, no amount of ebo will fix your problems. If you give happiness and share your possessions, you shall receive. This is the social effect, which brings us full circle back to the metaphysics of Oro.

Destiny is character; character is destiny

Ase

By awo dino

In Yoruba theology, perhaps nothing is more complex than the metaphysical concept of Ori, variously associated with the physical head (the cranium), personal Orisa, consciousness, destiny, human soul, and ancestral guardian angel. It can be considered as the Yoruba theory of consciousness, or as the Yoruba theory of destiny, or both. Our Ori serves as an umbilical cord connecting human with God (Olodumare). In order to begin to understand the Ori complex, we must start at the beginning, the Yoruba creation myth.

There are variations to the myth, and in fact there really are two separate story lines. One is cosmogenic and the other is political. The two became entwined into the most popular version below. Suffice to say at this point, the Ori (head) is to an individual what Olodumare is to the cosmos and a king to the body politic - a source of power. Hopefully, this paper while explaining the concept of Ori, will also provide a better understanding of the metaphysics of religious discourse; in this case the Yoruba religion.

Yoruba creation myth

Orisanla’ (Obatala’) was the arch-divinity who was chosen by Olodumare, the supreme deity to create a solid land out of the primordial abyss that constituted the earth and of populating the land with human beings. He descended from Orun (the invisible realm, the realm of the ancestors) into Aiye (the visible realm) on a chain, carrying a snail shell full of earth, palm kernels and a five-toed chicken. He was to empty the content of the snail shell on the water after placing some pieces of iron on it, and then to place the chicken on the earth to spread it over the primordial water by doing what chickens do, which is to scratch at the ground. According to this version of the myth, Obatala completed this task to the satisfaction of Olodumare. He was then given the task of making the physical body of human beings after which Olodumare would give them the breath of life (emi). He also completed this task and this is why he has the title of "Obarisa" the king of Orisas.

The other variant of the cosmogenic myth does not credit Obatala with the completion of the task. While it concedes that Obatala was given the task, it avers that Obatala got drunk on palm wine even before he got to the earth and he fell asleep. Olodumare got worried when he did not return on time, so he sent Oduduwa, Obatala’s younger brother, to find out what was going on. When Oduduwa found Obatala drunk, he simply took over the task and completed it. He created land. The spot on which he landed from Orun and which he redeemed from water to become land is called Ile-Ife, considered the sacred and spiritual home of the Yoruba. Obatala was embarrassed when he woke up and, due to this experience, he made it a taboo for any of his devotees to drink alcoholic beverages. Olodumare forgave him and gave him the responsibility of molding the physical bodies of human beings out of clay (in another version, Obatala was drunk when making the bodies and some came out a bit off. That is why Obatala is the Orisa of hunchbacks, and the disabled in general as well as albinos).

The making of land is a symbolic reference to the founding of the Yoruba kingdoms, and this is why Oduduwa is credited with that achievement. Oduduwa’s progeny were sixteen in number and became Kings. So Oduduwa was the first king of the Yoruba nation and founded Ile Ife, the ancient capital, creating a succession of kings all related to him.

However, this version incorporates history into the creation myth. It establishes the divine nature of the founder Oduduwa. Before the time of Oduduwa, the story did not involve Obatala getting drunk and Oduduwa finishing the job. What is important is the symbolism. The chain is representative of Ogun, the five toed chicken Osun, and the palm kernels, Orunmila. These Orisa, in combination represent unity and a balance of forces. Unity and balance (in a cosmos of dualities and diversity) become the central paradigm of Yoruba metaphysical thought. In Awo Fatunmbi’s words:

The world begins with one … the one that is formed through perfect balance between the powers of expansion and contraction, light and dark, … the balance between the masculine and feminine powers … and that one is a microcosm of all that is…

He has compared the chain to the double helix of DNA and the pieces of iron to Ogun as the primer of evolution. According to modern science, iron molecules at the bottom of the ocean are believed to have interacted with oxygen to create the first organisms on earth. Continuing the creation myth, Obatala was successful up to a point. He was unable to create civilization because he lacked the proper technology. Ogun was called in to continue the job. But Ogun, although very good at establishing civilizations, is not good at “running” them. In comes Orunmila to establish ethics and order; to temper Ogun’s primal energy. Obatala creates, but it is Ogun who moves creation, Ogun is evolutionary energy.

Keep in mind that Orisa and other entities featured in Yoruba myths, itan and Odu bear deep philosophical connotations that begin from the metaphysical meaning descending into the aesthetic and then epistemological through to ethical meanings and, eventually, to positive or negative social effects (it is easy to get caught up in the personalities themselves). Individual metaphysical phenomena come together as a unity of substances in a universe of relativistic existence (Okunmakinde). This idea is expressed in the most compelling part of the story; the Snail Shell full of earth-dust.

In the Odu Okanran Ogunda there is another version of the creation myth that is not well known. In this version, it is Orunmila (the Prophet, Orisa that represents Olodumare’s wisdom) who carries the snail shell full of the substance which creates land upon the primordial waters. The Snail Shell was taken from the seat of Olodumare and given to Orunmila with the authority to create the earth. In the process of creation, Orunmila dipped his hands into the snail shell and took out measures of earth-dust (Oro, primordial matter) with which land was created on the primordial waters.

Odu Ifa Osa Ogunda

There-were-no-living-things

Was the priest on earth

That-which-was-suspended

But-did-not-descend

Was the priest in heaven

All-was-just-empty-space

With-no-substance

Was the priest of Mid-Air

It was divined for Aiye and Orun*

When they both exited

With no inhabitants

In the two empty snail shells,

There were neither birds nor spirits

Living in them

Odumare then created himself

Being the Primal cause

Which is the reason we call Odumare

The only wise one in aiye

He is the only cause in creation,

The only wise one in Orun,

Who created humans.

When He had no companion,

He applied wisdom to the situation

To avert any disaster.

You, alone,

The only one in Orun

Is the name of Odumare

The only wise one,

We give you thanks,

The only knowing mind,

You created man.

Listening to one side of an argument,

You judge, and all are pleased.

Ase

*Aiye is the visible realm; Orun the invisible realm. Most confuse these two words to mean earth and heaven. Hopefully, when you finish reading this material, you will be able to come back and make sense of the above ese (verse) Odu.

In Odu Ifa Osa Ogunda, part of a verse says, “Iri tu wili tu wili la fi da ile aye, la bu da ile,” which means, “Dews pouring lightly, pouring lightly, was used to create the earth world in order that goodness could come forth into existence at once.” The dew drops are particles of Oro – primordial matter - contained in the snail shell. Once empty, it remains as the representation of the base of causation from which matter derived. The “goodness” speaks to eniyan – human beings, which brought goodness to earth. The oro then melted and was suspended in mid-air (referred to in the above Odu verse as the “priest of mid-air”). Oro then dropped;

Oro, the cause of great concern for the wise and experienced elders

It sounds, “Ku” (making the heart miss a beat)

“Ke” (as a ponderous object hitting the ground)

“Gi” (making the last sound before silence)

and “La”, with a loud cracking sound is transformed into a new state called “Ela.”

Ela is part of the Orunmila complex. Orunmila can be considered the anthropomorphic representation of Olodumare’s wisdom - ogbon, knowledge – imo, and understanding – oye; the most powerful particles or elements in the earth-dust or droppings. Orunmila’s connection to Ori is fundamental to the Ori complex. He is “Eleri Ipin”, the deity of fate. He was present at the moment of creation, and thus knows the fate of every Ori. He acts as the mediator between a person and their Ori through his ability to speak the words of Ifa as they relate to the individual Ori and its destiny. Ifa is the Oracle. Ela is that invisible energy that moves between the oracle and Orunmila, and between Ori and Olodumare – the umbilical cord. Ela is Oro after it hits the primordial abyss. Oro, as primordial matter, has an innate urge to communicate.

The oro that drops from the elderly is stupendous

It was divined for oro-oro-oro

Who did not have anyone to communicate with and started groaning

HOORO, HOO-ORO! (Ogbon, Imo, Oye, descend!)

Olodumare made HOO (Ogbon, Imo, Oye)

HOO descended to become Hoo-ro (I can’t help but notice the similarity between Hoo-ro and Horus)

Ela made Oro digestible and useful to human needs

Ela is the manifestation of the primal urge to communicate. It is the link between human and God; human and human; and human and the universe. This extensionistic conception, prevalent in all religions, is Oro, which manifested is Ela. Its individual manifestation is Ori. The Snail can be viewed as the principle of natural extensionism which forms a basis for that which can be seen and that which cannot; the physical Ori (your skull), and Ori-inu (consciousness, soul). There is a Yoruba phrase, Ori-Ooro, which means, “head at dawn,” dawn being the beginning obviously. Thus, Ori is Oro, and Oro is Ori:

Ori lo nda eni

Esi ondaye Orisa lo npa eni da

O npa Orisa da

Orisa lo pa nida

Bi isu won sun

Aye ma pa temi da

Ki Ori mi ma se Ori

Ki Ori mi ma gba abodi

Ori is the creator of all things

Ori is the one that makes everything happen, before life happens

He is the Orisa that can change humans

No one can change the Orisa

Ori, the Orisa that changes the life of man with baked yam (abundance)

Aye*, do not change my fate (* Aye - unity of the forces of good and evil)

Ori do not let people disrespect me

Ori do not let me be disrespected by anyone

My Ori, do not accept evil

This extensionalistic concept (from God to human), that our Ori is composed of a portion of Oro (each Ori receives a portion with its own special combination of elements contained in the earth-dust – oro - from the snail shell, thus each ori’s individuality) is further elucidated in the sayings, Ori lo da ni, enikan o d’Ori o (It is the Head that created us; nobody created the Head), and Ori eni, l’Eleda eni (one’s Head is one’s Creator), and also in the following oriki:

Ori lo da mi

Eniyan ko o

Olorun ni

Ori lo da mi

Ori is my Creator

It is not man

It is Olorun (Olodumare)

Ori is my Creator

Olodumare made Hoo, which is comprised of three of the most powerful elements contained in the “earth-dust” sprinkled from the Snail shell – Ogbon (wisdom), Imo (knowledge), and Oye (understanding). “Ro” means descend, as in the chant, Ela ro, Ela ro, Ela ro. It is said that Olodumare created Ogbon, Imo and Oye as an intermediary force for creating more beings. IT tried to find a place for them to live, but they came back to IT, humming, and Olodumare swallowed them. They hummed inside IT for millennia, so IT had to get rid of them. Olodumare ordered them to “ro” descend, saying, “hoo-ro.” Oro, the solid matter, melted and was suspended in mid-air like jelly. Oro then dropped and “la” cracked into a new state called E-la, or Ela. Ela (the Spirit of Purity) functions in the Ifa divination complex as the embodiment of Ogbon, Imo, and Oye. Ela is the recognized authoritative source of communication and explanation of the nature of Olodumare and all ITs creation (Abiodun).

Who was the first to speak?

Ela was the first to speak.

Who was the first to communicate?

Ela was the first to communicate.

Who is this Ela?

It was the Hoo which descended

That we call Ela.

In Odu Ogunda Ogbe, we find more references to Snail and Oro:

He Made Divination for the Snail in Orun

Aba she kere mu legun, Odifa fun ibikunle to ma nu kan kunle ara le

The-umbrella-tree-is-short-when-young-but-a-little-later-it-will-become-taller-than-the-roof-of-the-house. That was the name of the Awo who made divination for Ibikunle, when she was single-handedly going to populate her house by herself. Ibikunle is the heavenly name of the Snail and it means the one who produced enough children to fill his or her house. She was advised to make ebo with hen, rat and fish. She made the ebo and began to produce children to fill her house. When it appears at divination for a woman anxious to have children, she will be advised to make ebo because she will have so many children that she will eventually be tired of having more.

He Later Divined for his Friend Oro

Okon kpoki, Erigidí kpií, adita fun Oro nijo ti Oro wo orun kenge kenge.

One-sharp-sound and one-loud-sound (“Ku” and “Ke”)are the names of the Awos who made divination for Oro when he was so ill that he thought he was going to die, (figure of speech) when he was looking forlornly at Orun from his spot hanging in the air. He was advised to make ebo with eko, akara, rat, fish and a chicken. After preparing the ebo, the Ifa priests told him to carry it on his head (ori) to Esu’s shrine. He was further told that on getting to the shrine, he was to back it and incline his head backwards in such a way that the ebo would drop on the shrine (acknowledging Esu as that liminal space between orun and aiye, dark and light).

As soon as he allowed the sacrifice to drop on the Esu shrine, while still backing up to Esu, a voice instructed him to stretch his hands and feet forward. First, he stretched out his left limbs and next his right limbs (with Esu’s help, he makes the transition from the invisible plane to the visible plane. Left limbs darkness, right limbs light). The moment he did that, the disease that had afflicted his body to the point of incapacitation suddenly disappeared. From the shrine, he began to dance and sing towards the house in praise of the Awo. The Awo praised Ifa, and Ifa praised Olodumare. When he began to sing, Esu put a song in his mouth:

ljo logo ji jo, erigidi kpii, erigidi.

ljo logo ji jo, erigidi kpi-kpi-kpí, erigidí.

He was singing in praise of Orunmila and his two surrogates for the miraculous healing he had just experienced. When this odu appears at divination in ibi (negative manifestation) the client will be

told that he or she is suffering from a disease which he or she is concealing, but will be advised to

make ebo to get rid of it. If the indication is ire (positive manifestation), then the person will be told to be expecting some gift or favor.

In the ese (verse) above regarding Snail, we see that Snail is also known as Ibikunle, “the one who produced enough children to fill his or her house.” This is a praise name. It refers to the the Snail’s role in creating everything in the universe, in this case the earth including humans. In the verse following the one about snail, regarding Oro, we find in the names of the Awo, reference to the sounds of Oro dropping and becoming Ela (the Spirit of Purity which represents Ogbon, Iwo and Oye).

Ela speaks through Owe (proverbs, Odu, oriki, chants, ofo ase, etc.), and Aroko (coded symbolic messages- drums, sculpture, dance, song, poetry, etc.). Owe is the horse of Oro; if Oro gets lost, Owe is employed to find it.

ORÍKÌ ELA

Ela ro, Ela ro, Ela ro (ro – descend)

Ifa please descend

Ela, please be present

If you are in the Ocean,

please come

If you are in mid-lagoon,

Please come

If you are on the hunt,

Please come

Even if you are at Wanran in the East

Where the day begins

Please come

Come urgently, Ela

ase

The awo, or diviner, must develop the ability not only to invoke Ela, but to align Ori with Ela. Ela is that substance that is extensionalistic; that connects our inner self in the visible plane with our higher self on the invisible plane. The historical prophet Orunmila was an incarnation of the Spirit of Ela and the alignment of Ori with Ela is known as returning to the time when Orunmila walked the earth. This alignment occurs as a result of consistent attention to the Ifa discipline of chanting oriki (communication). Alignment with the Spirit of Ela is the blessing of Ifa and chanting is the road to that blessing (Fatunmbi). In order to work with one’s Ori, Ela must be invoked first.

The Ori complex

As we continue with the Yoruba creation myth, we now come to the creation of human beings. Obatala’ who is equally referred to as Orisa-nla’ (the arch divinity), is said to have been charged with the responsibility of sculpting the human being “eniyan” and designing only the body: hence his appellation a-da-ni bo ti ri (he who creates as he chooses). After finishing his work, Olodumare then breaths (emi – life force) life into the body. The eniyan then proceeds to Ajala-Mopin – Irunmole to o nmo ipin (the divinity who moulds ipin) ipin is that portion of oro, the “God-matter” apportioned to each Ori by Ajala-Mopin. Ipin is destiny. In Ajala’s “shop,” the eniyan (person) selects for himself his ipin (portion), commonly referred to as Ori-inu (inner head). Here we have the separation of body and mind, or soul. Presumably, the choice of heads (Ori) is based on what one wants to accomplish in the coming lifetime. This Ori–inu or ipin is the individual’s chosen destiny. There is some variance in this part of the myth. Some say you get your Ori from Ajala but then go to Olodumare and tell IT what you want to accomplish in this lifetime, and the deal is sealed. Some say that humans obtain their ipin (portion, destiny) in one of three ways; by kneeling down and choosing it, a-kun-le-yan (that which one kneels to choose), by kneeling to receive, a-kun-le-gba (that which one kneels to receive), or by having his destiny apportioned to him a-yan-mo (that which is apportioned to one). Others, myself included, believe akunleyan, akunlegba and ayanmo are component parts of Ori-Apere. (one half of Ori) Regardless, all acknowledge the Yoruba belief in predestination and also establish the belief in Ipin (portion) as a person's destiny which he chooses during his pre-existent state. It is this destiny that is seen as metaphysically constituted in Ori-inu (inner head) and it is this that man comes into the world to fulfill. This belief manifests itself in the maxim Akunle-yan ni ad’aye ba (the destiny chosen is that which is met and pursued) (Abimbola).

The Yoruba believe that creation exists on two complementary planes: the visible world, called aiye, the physical universe that we inhabit, and the invisible world, called orun, inhabited by the supernatural beings and the "doubles" of everything that is manifested in the aiye. These planes are not to be confused with heaven and earth. There is not a strict division; they exist in the same space. The aiye is a "projection" of the essential reality that processes itself in the orun. Everything that exists, exists in orun also. Actually, orun is the reality and aiye the mirror image. It is necessary to understand that aiye and orun constitute a unity, and as expressions of two levels of existence, are undivided and complementary. There is full identity between them; one is just an inverted image of the other (Teixeira de Oliveira).

The Ori complex is comprised of three parts; the Ori - Consciousness; Ori Inu - the Inner Self; and Iponri - the Higher Self. Much has been written regarding the concept of Ori. I break it down using the theory of extensionalism, which simply states that humans are connected to God in some manner; that there is communication; that we are in fact extensions of God. This idea is common to most metaphysio-religious systems. In Yoruba thought we have the concept of Oro. At the level of the individual, the concept is expressed in the Ori complex (or soul complex) – an extensionalistic construct that explains the interaction between tangible and intangible existences. As Orun and Aiye exist simultaneously in the same space, so does the human soul in the form of Ori-inu and Iponri. Matter-mass which makes the transition from orun to aiye through the snail shell produces a double existence. The fragments or portion that a person receives (ori-inu) from Ajala-Mopin in his or her Ori is brought with the person to aiye, the visible realm and to Ile (earth). The original stays in orun. This original is called the Iponri or Ipori. It is our Iponri that allows blessings to flow from “above.” No Orisa can bless us without permission from our Ori. Why? Because our Iponri is our real self, our beginning and our end. Any thing we wish to manifest in life, must be created by our Iponri first in the invisible realm, where all things are created before manifesting in the visible worlds. Thus the popular chant from Odu Ifa:

Ko soosa

Ti i dani i gbe

Leyin Ori Eni

No divinity

Can help, deliver, or bless one

Without the sanction of one’s Ori

Our wishes, wants, fulfillment of needs, prayers, etc., must originate in orun before they can manifest in aiye. Our Ori, the third component of the Ori complex, serves as our individual “Ela,” that which connects our dual selves that exist simultaneously in the invisible and visible worlds. Ori is that intangible substance that is the extension, the communication, across the divide. That is why we portray Ori as our personal Orisa, because Ori carries our prayers and communicates our wishes to our Iponri. In this way, our Ori is like an Orisa pot. It is our connection to ase. This is why Ori is the first “Orisa” to be praised (Ori isn’t really an Orisa), it is the one that guides, accompanies and helps the person since before birth, during all life and after death, assisting in the fulfillment of his or her destiny. Ori-Apesin; one who is worthy of worship by all. It is said that a person’s Ori, besides being the source of ire, is the only Orisa that can and will accompany one to the very end:

Bi mo ba lowo lowo

Ori ni n o ro fun

Orii m, iwo ni

Bi mo ba bimo l’aiye

Ori ni n o ro fun

Orii m, iwo ni

Ire gbogbo ti mo a ni l’aiye

Ori ni n o ro fun

Orii m, iwo ni

Ori pele

Atete niran

Atete gbe’ni k’oosa

Ko soosa ti I da’ni I gbe

Leyin Ori eni

Ase

It is Ori alone

Who can accompany his devotee

to any place without turning back

If I have money, it is my Ori I will praise

It is my Ori to whom I shall give praise

My Ori, it is you

All good things I have on Earth

It is Ori I will praise

My Ori it is you

No Orisa shall offer protection

without sanction from Ori

Ori, I salute you

Whose protection precedes that of other Orisa

Ori that is destined to live

Whosoever’s offering Ori chooses to accept

let her/him rejoice profusely

Ori the actor, the stalwart divinity

One who guides one to wealth, guides one to riches

Ori the beloved, governor of all divinities

Ori, who takes one to the good place

Ori, behold the good place and take me there

Feet, behold the good place and accompany me thereto

There is no divinity like Ori

One’s Ori is one’s providence

My Ori, lead me home

My Ori, lead me home

Ori, the most concerned

My skull, the most concerned in sacrificial rites

Ori, I thank you

Ori, I thank you for my destiny

My skull, I thank you for my destiny

Ori I thank you (mo juba)

Ase

As the “personal Orisa” of each human being, our Ori is vital to the fulfillment and happiness of each man and woman; more so than any other Orisa. More than anyone, it knows the needs of each human in his or her journey through life. Ori has the power of Ela, to pass freely from Orun to Aiye and vice versa. It exists on both dimensions:

Ire gbogbo ti ni o nii

N be lodo Ori

A lana-teere kan aiye

A lana-teere kanrun

All the good that I am expecting is from my Ori

He who makes a narrow path to aiye

He who makes a narrow path to orun

What at first glance seems like a very complicated theology, when we gain an understanding of the metaphysics within the mythology, reveals a simple metaphysical principle; the principle of causation. The ability to create in Orun, and have it manifest in Aiye; like Oro becoming Ela. Awo is the development of this ability; either through our Ori, through Orisa, ancestors, etc. Others have expressed the concept of Ori. One explanation worth quoting is by Babasehinde Ademuleya:

"The soul, to the Yoruba, is the “inner person”, the real essence of being – the personality. This they call “ori”. The word “ori”, in contrast to its English meaning as the physical “head”, or its biological description as the seat of the major sensory organs, to the Yoruba connotes the total nature of its bearer. A critical study of the term in Yoruba belief reveals the intrinsic meaning and value of the object it is identified with – that is, the physical head – and carries with it the essential nature of the object associated with it – that is the man. To the Yoruba the physical “ori” is but a symbol – a symbol of the “inner head” or “the inner person”, the “ori-inu” (the inner head). Ori in Yoruba belief occupies the centre of sacredness, and how it is conceived is embedded in the Yoruba myth concerning the creation of man and the role played by his creator, Eledaa (He who created). The Yoruba word for man – eniyan – is derived from the phrase eni-ayan (the chosen one)."

… a wa gegebi eniyan, …

a wa ni Olodumare yan

lati lo tun ile aye se,

Eni -a yan ni wa...

we as human beings,

we are the God’s elect,

designated to renew the world,

We are the chosen ones.

Human beings are called eniyan (the chosen ones) because they are the ones ordained "to convey goodness" to the wilderness below Olorun. In other words, divinity abides in humanity, and vice versa.

Let us now consider the Ori-inu. The African idea of the soul has been conceived and described in different ways. In Yoruba, the idea of the transcendental self, or soul, has been difficult to express in English. Some have called emi soul. Emi is invisible and intangible. This is the life force breathed into each human by Olodumare. Not to be confused with eemi, which is simply breath. Emi is what gives life to the body. When it ceases, life ceases. A Yoruba would say about a corpse, “emi re ti bo” - his emi is gone. But it is not soul. Another word sometimes mistaken for soul is okan, which literarily means the heart. For the Yoruba, the heart is more than an organ that pumps blood. It is from where our emotions emanate, and the locus of psychic energy. But it is not soul. Both of these interpretations are wrong. The soul, to the Yoruba, is Ori-inu, that portion of the “God-stuff” from the Snail that comprises the “inner person”, the real essence of being.

Regarding life-force, that which Olodumare bestows on each individual and an integral component of each Ori-inu, it is known as ase (pronounced awshay). Emi is the life force, but it is made up of ase. Ase is a concept almost as complex as Ori. Ase is a component of the life force breathed into each human being by Olodumare; it is spiritual power; it is the power to create. Pemberton describes it this way: